Why Foreskin Activists Are Taking to the Streets.

At the anti-circumcision trucks in NYC, come for the sex and stay for the graphic snip videos

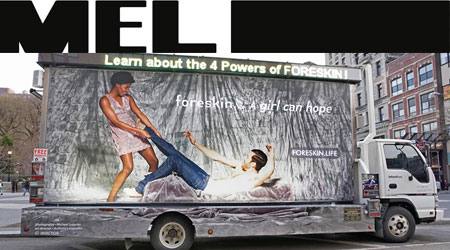

Passersby in Manhattan’s Union Square are no strangers to public stunts. They’ve got high-flying skateboarders, activists, rallies and protests — and this week, a giant truck featuring a half-naked woman ripping the tighty-whities off a helpless dude. At the top are the words “foreskin… a girl can hope.” To the right, there’s a big ad sending onlookers to a site called foreskin.life, which promises a list called “4 Powers of Foreskin” and shows the intertwined legs of a couple in bed.

The group behind the truck is an anti-circumcision group called Intaction — like the words “intact” and “action.” Led by Anthony Losquadro, they’ve dedicated their time to fighting, or at least starting a conversation around, infant circumcision.

“Ninety-nine percent of European men are intact, and right now in America, the rates are closer to 50/50,” Losquadro says. “Thankfully the rate is beginning to decline, and our job is to drive that down to be as low as the European rates.” Though circumcision is a polarizing subject (you can read our extensive guide to it here), Losquadro claims he’s only there to educate the masses. That’s where the truck comes in.

After Intaction lures you in with the sexy stuff, they want you to watch graphic videos of babies getting snipped. “In addition to the main billboards, our mobile unit has exhibits such as the Infant Genital Cutting Exhibit, where people see what’s done to a baby in a hospital. It’s what the doctor won’t show you goes on behind closed doors — and that’s one of our most popular exhibits.”

After you’ve peeked behind the doctor’s curtain, head over to the truck’s historical exhibit: “Completely Bizarre History of American Circumcision.” Losquadro tells me all about circumcision’s history as a 19th-century anti-masturbatory procedure. My own research finds that John Harvey Kellogg, the cereal guy who was also a doctor, prescribed circumcision without anesthesia as a punishment for self-abuse.

As circumcision rates have fallen in the U.S. and intactivists spread their message further, foreskin-rights groups have been the subject of criticism — particularly for a broad insistence on calling circumcision “genital mutilation” and equating it with the more sadistic practice of female genital mutilation, or FGM. According to a joint statement from the U.N. and the World Health Organization, FGM is a human rights violation with no medical benefits. “Painful and traumatic,” it “interferes with the natural functioning of the body and causes several immediate and long-term health consequences.”

As for male circumcision, the WHO says male circumcision (in babies) results in a “very low rate of adverse events,” especially when performed by well-trained medical professionals.

Other doctors argue that circumcision actually provides health benefits, though research is ongoing. Pediatric urologist Anne-Marie Houle writes in the Canadian Urological Association Journal that circumcision can lower the risk of HIV, STDs and UTIs. She and many others provide evidence that circumcision actually improves sexual function and sensation. Houle also argues circumcision can help protect against penile cancer, as it removes the risk of phimosis (an inability to retract the foreskin), which is a risk factor.

Still, the intactivist scene continues to gain steam online. Some men try their hand at underwear that simulates foreskin, and some are on a quest to regrow their foreskins by hanging weights from their glans — take it from Wayne Griffiths, the “father of foreskin regeneration.” But according to Intaction, that’s not what their mission is about, nor are they trying to get to Capitol Hill. “We’re just conducting advocacy and educating,” Losquadro says.

Going on four years of public activism, the intactivists aren’t leaving Manhattan anytime soon — or at least until American circumcision rates match Europe’s. “We’re in Union Square every month, sometimes twice a month, until the winter weather shuts us down,” Losquadro says, adding that New York City’s size and diversity give them something like a perpetual focus group.

And so, the debate rages on in Union Square, in doctor’s offices and online. Intactivists like Losquadro say they’re just trying to tell their side of the story (though some activists have shown to be a bit more aggressive than that), while urologists and health organizations urge each individual to weigh their options and know the benefits.

In other words, it’s the classic example of an issue that cuts both ways.

Quinn Myers is a writer based in Chicago.

The worldwide rates of sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS, are lower than they are in the USA, where the majority of males are without foreskin. And here,instead of touting the protective, immunological, sensual, and sexual benefits of the structures, functions, development, and care of the normal penis and telling parents about the physical and psychological harm of amputating a normal part of a non-consenting child’s body, this billion-dollar-a-year industry is perpetuated by healthcare professionals who continue.to bombard the public with the mythical benefits of amputating the foreskin. Shame on them!

If a grown man wanted to take advantage of the claimed “health benefits” of male genital mutilation, he is perfectly free to do so.

Forcing this on a newborn infant is absolutely disgusting!

In the absence of an immediate medical condition, the removal of healthy and functional tissue from a BABY’s normal intact penis, is NOT a “medical” procedure; it IS mutilation through and through.

Perhaps you are not aware that at least 100 babies die every year from being subjected to this completely unnecessary “surgery”!

DEATH DUE TO MALE INFANT GENITAL MUTILATION (aka “circumcision”)

“The most stunning revelation about circumcision deaths came from one of this country’s most highly respected and decorated pediatricians, Dr. Sydney S. Gellis, of the Department of Pediatrics at the New England Medical Center Hospital in Boston. Dr. Gellis was honored as a “Pediatric Pioneer” at the 1996 American Academy of Pediatrics annual meeting in Boston. 78

In a famous article in a leading American pediatrics journal, Dr. Gellis revealed that: It is an incontestable fact at this point that there are more deaths each year from complications of circumcision than from cancer of the penis. 79

Explaining how circumcision deaths are covered up, Dr. Gellis later expanded his revelation, stating: A number of deaths from circumcision are signed out as deaths due to sepsis [blood poisoning]. 80

Circumcision deaths are also disguised as deaths due to “complications of anesthesia” without mentioning in the death charts that the baby had been anesthetized for no other reason than for an unnecessary routine circumcision. 81

One way that hospital administrators have tried to cover up these deaths is by omitting any reference to circumcision on the baby’s death chart. The deaths are usually blamed on something else. For example, infections that lead to death are generally caused by meningitis, 82 streptococcus infection, 83 systemic blood poisoning, or gangrene. These organisms enter the amputation wound because it provides easy entry rather than because the child is predisposed to infection.

…

It would be one thing if circumcision were the best and only weapon against a horrible, highly contagious epidemic disease that was killing innocent people in large numbers. Under these circumstances, a few collateral deaths might be justifiable. But circumcision is unable to prevent any disease, and, besides, the diseases that circumcision is alleged to prevent are all related to poor lifestyle choices.

Even if you were to accept the statistics waved about by circumcisers, the difference in the rates of disease between intact and circumcised males is infinitesimal. The fact that none of these diseases are highly contagious epidemic diseases that kill innocent people in large numbers proves that the killing of even a single baby during circumcision is completely unjustifiable.”

~*~

From this book:

What Your Doctor May Not Tell You About Circumcision: Untold Facts on America’s Most Widely Perfomed-and Most Unnecessary-Surgery

~ by Paul M. Fleiss, Frederick M. Hodges.

Start reading it for free:

http://a.co/bTsL397

~*~