| Circumcision & HIVAIDS | A Life-Saving Cut?

By Michael Obert, for GEO Magazine

The World Health Organization (WHO) wants to have 20 million men in Southern and Eastern Africa circumcised. WHO officials claim that circumcision will prevent HIV infections. To convince them to undergo the operation, men are assured that without a foreskin they will be “vaccinated against AIDS.” It is an unprecedented undertaking: never before have aid organizations attempted to surgically alter so many people. It could end up being an unprecedented disaster.

ERNEST CHISHA hangs his pants on the door handle and lies back on the table, his head resting on a dirty foam pad. His breathing accelerates. Except for his dusty socks, the 30 year old is naked.

“Why do you want your foreskin removed?”, asks a lanky man – referred to as “the provider” – while he takes a syringe out of the package with his white rubber gloves. He injects eight times, right under the glans. “I want to protect myself from the virus,” Chisha groans. “I just don’t want to get AIDS. I want to live.”

The anesthetizing of Ernest Chisha’s penis in the circumcision room of the Chilenje Clinic in the Zambian capital of Lusaka, is the beginning of a medical procedure being performed millions of times in Southern and Eastern Africa. In the fight against HIV, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations are calling for an unprecedented campaign of prevention. Their goal: to have 20 million 15-49 year-old men, in 14 African countries, circumcised by 2016. It will cost international funders – primarily the US President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – as much as two billion dollars for what is easily the largest series of surgeries in world history.

All of this is because having their foreskins removed provides African men with a 60 percent reduction in their risk of contracting HIV via unprotected vaginal intercourse. So claims the WHO. Should the campaign be successful, 3.4 million new HIV infections would be prevented between now and 2025. But critics warn that the mass circumcisions are based on disputed studies, and could end up having the opposite of the hoped-for effect: more HIV infections.

African men entering circumcision clinic

Zambia, a landlocked country in Southern Africa, is one of the prototype countries for the campaign. More than 840 000 Zambian men have already had their foreskins removed. The national head of the WHO, Olusegun Babaniyi, praises the numbers as a “significant success.” Zambia, with 12.5 percent of 15-49 year-old affected, has one of the highest HIV rates in the world. A Zambian is infected with HIV every seven minutes. There are more than half a million AIDS orphans in the country of just over 15 million people.

A SEVEN HOUR DRIVE south of Lusaka, in a town called Sichiyasa just a few kilometres from the famous Victoria Falls, Margaret Nkunika trudges in her city shoes through a harvested maize field. Thatched clay huts shimmer on the savannah. Plumes of dust whirl in the wind. The fifty-something woman with a head of untamed Afro-style hair is what they call a “mobilizer,” deployed by the thousands into remote regions to persuade men.

“We are circumcision agents,” says Margaret Nkunika to a group of maize farmers, who are sitting under an awning carving animal sculptures for tourists. “Circumcision gives you 60 percent protection against HIV! 60 percent, people! 60 percent!” It sounds like a silver bullet.

AIDS claimed more than one million dead in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2013. 25 million people here live with HIV, which triggers the immunodeficiency disease. Nearly three quarters of global infections occur in this region. “Both my sisters and my husband died of AIDS,” says Margaret Nkunika. As a mobilizer, she goes from town to town and house to house several times a week, without pay. “Had they known that circumcision could have protected them, they would still be alive.”

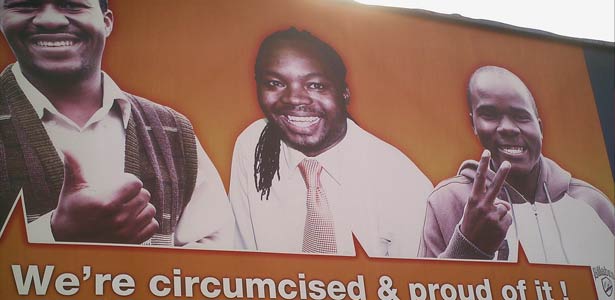

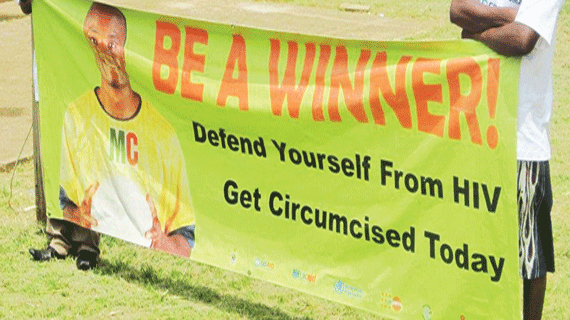

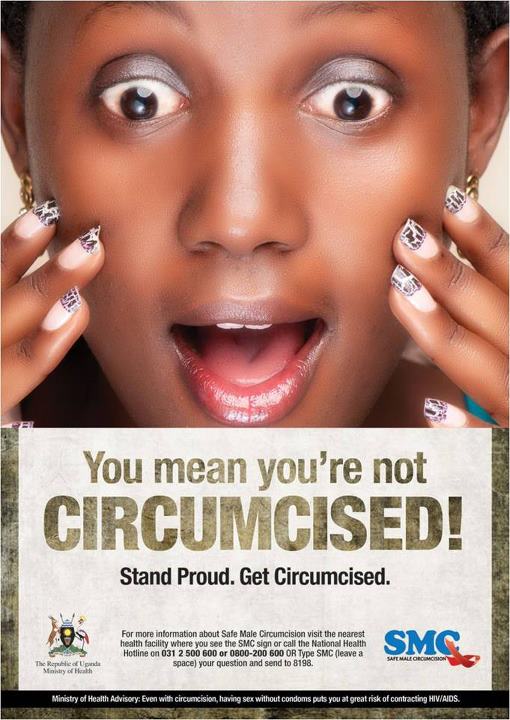

The fieldworkers’ efforts to convince people are supported by a multi-million dollar advertising campaign. In the streets of Lusaka, huge posters display the silhouette of a man standing confidently with his thumbs tucked into his belt; it reads: “Circumcision – a man who cares!” Famous musicians declare on TV that they’ve undergone the procedure. “Hello, I’m Chief Mumena!” says the tribal chief of the Kaonde people in a commercial; in his hand he holds a scepter made of ivory. “Get yourselves circumcised today! For more information, dial 990.”

In Zambia’s neighbouring country of Zimbabwe, elected officials are having themselves circumcised to set a good example. At public festivals in Uganda, men can win bicycles or electric generators if they allow themselves to be circumcised.

In hard-to-reach mountain regions in the small nation of Swaziland, music blares out from truck sound systems, the DJ’s calling out through the microphone: “Circumcision doesn’t hurt! Go to the tent and get yourself registered!” In bordering South Africa, actual circumcision factories are emerging, in which doctors go from bed to bed cutting off foreskins – as many as ten per hour – like in an assembly line.

“A single harmless operation, that never has to be repeated, can save your lives,” explains Margaret Nkunika to the maize farmers in Southern Zambia, as they crouch in front of her on the floor. She holds her little finger up , as if the last section were the glans: “Your foreskin is a deadly hazard,” says the circumcision agent, and slices it with an imaginary knife. “Clean! Healthy! Safe!”

CIRCUMCISION – the total or partial removal of the male foreskin – is carried out in some parts of the world, first and foremost for religious reasons. Even the ancient Egyptians cut their men: cultural historians suspect that this was meant as a symbolic representation of snakes, who were considered immortal on the banks of the river Nile, owing to their ability to cast off their skin and renew themselves again and again.

In Judaism as in Islam, the circumcision of boys is considered a matter of religious identity. Even many evangelical Christians, primarily in the USA, have their foreskins removed because they want to follow Jesus, who they assume, as a Jew, would have been circumcised. For decades, the circumcision of newborns in the USA – for medical or esthetic reasons – was paid for by health insurance funds as a routine procedure.

However this trend is currently being reversed. Circumcision came into fashion in Western Europe in the 1970’s, to prevent against narrowed foreskins, and because a circumcised penis was supposed to be more hygienic than an intact one, as many people today still assume.

The first sign of a connection between foreskin and HIV were in the mid 1980’s. Scientists noticed that fewer circumcised men were infected, and construed that the foreskin was a possible point of attack for the virus. The inner foreskin is an area of concentration of lymphocytes, and specialized cells called Langerhans cells. These specialized immune cells actually serve to protect against infection. So, while Langerhans cells normally intercept and destroy HIV, under other conditions – for example in the presence of parallel infections – they can relay the virus on the HIV target cells, and raise the infection rate.

Then, in 2005 came the report, “Male circumcision protects against HIV like a vaccination.” A sensation! Hope bubbled up everywhere. The catalyst for the euphoria was the French Doctor Bertran Auvert. For his study in South Africa, 1339 men in the Johannesburg township of Orange Farm were voluntarily circumcised. After the procedure, Auvert compared their infection rate with a control group of 1309 non-circumcised men in the same region. His hypothesis was that the HIV target cells, and thereby the risk of infection, could be eliminated along with the foreskin.

After one and a half years, he appeared to prove his theory correct: Among the noncircumcised men in the control group, Auvert assessed 49 cases of HIV, while he found only 20 among the circumcised men. From this, the Frenchman inferred an up-to-60-percent reduced HIV risk, which was soon to become the mantra of the WHO campaign in Africa.

Researchers in Kenya and Uganda yielded similar results. The WHO declared the results a milestone, and in 2007 recommended that voluntary circumcision of men be promoted in 14 countries with high HIV rates, including: Zambia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya. Since then, about six million African men have had their foreskins removed.

“TOTAL NONSENSE,” says the German circumcision expert Wolfgang Bühmann. “Condoms offer almost complete protection against HIV. So why a surgical intervention?” Bühmann is a spokesperson for the Professional Association of German Urologists. He has personally performed more than 1000 circumcisions – however for medical reasons, on boys with painful foreskin-narrowing, and to remove inflammation. In the treatment room of his practice on the North Sea island of Sylt: couches, ultrasound machines, white walls.

“These circumcisions in Africa are not only futile, but potentially deadly,” warns Bühmann.

“To help people in areas with high HIV rates, you have to make it clear to them: sex without a condom is life-threatening. Sex with a condom, however, is safe, regardless of whether the foreskin is still there or not. Shades of grey in-between just create confusion.”

(ARTICLE CONTINUED BELOW)

WHAT KIND OF CIRCUMCISION IS IT?

Male vs Female Circumcision

The UN and other organizations are supporting the mass circumcision of men with billions of dollars. The same institutions are simultaneously fighting the circumcision of girls and women with all of their might. Is this unequal treatment justified?

Circumcision Overview

Female circumcision is a crime in many countries. The mutilation of female genitals is a violation of human rights. This damaging tradition is nonetheless widespread in 29 countries, primarily in Africa. 24 of these countries have already passed laws forbidding female genital mutilation. And yet it is still so widespread that the next 10 years will likely see another 30 million women and girls circumcised, on top of the current number of 130 million.

The exact approach of male and female circumcisers varies significantly across different regions: the practice of female circumcision ranges from puncturing or clipping the clitoral foreskin to the removal of the clitoris and inner labia, and as far as the so-called “pharonic circumcision,” an exceptionally brutal operation in which all external parts of the vulva are severed and the vulva reduced to a tiny hole. Many victims, not only of the more extreme forms, suffer lifelong consequences from these utterly painful and traumatizing procedures.

The cutting of men’s foreskins is subject to much less ostracism. Yet, the implications are still significant, even simply because of the scale of the phenomenon: one third of the global male population is circumcised, approximately one billion men and boys. This is primarily for religious and cultural reasons, seldom for medical purposes. The majority of circumcised men and boys are Muslims, but also 60 percent of newborns in the USA are circumcised (a declining trend), and in South Korea 76 percent of 14-29 year olds are cut. As is the case with girls, circumcision of boys is frequently so deeply entrenched in society as a rite of initiation, that parents are under considerable social pressure to have the procedure carried out.

Circumcision can likewise involve quite different procedures: from clipping the end of the foreskin, to the total removal of the foreskin, and even what is called sub-incision, a rather rare procedure that requires cutting the whole length of the penis to slice open the urethra.

Circumcision Related Health risks for both genders

Nearly all forms of circumcision are accompanied by significant health risks, particularly when the operation takes place in often unhygienic traditional settings. This goes for male circumcision as well. In South Africa, between 2008 and 2014, approximately half a million boys were treated in hospital for botched circumcisions, and more than 400 of them died. Even in very good hygienic conditions, medical problems are often noted, including deformed scarring, hemorrhage, wound infection, diminished sensation, and other consequences. Even if the dramatic consequences are more obvious with women and girls, the effort to circumcise the majority of men in Southern Africa may, even by a conservative estimate, lead to hundreds of thousands of complications, some of them lifelong.

In Germany, lawmakers have already given a clear answer to the question of how female and male circumcision should be addressed. Genital mutilation of women was made a criminal offence in 2013, while at the same time the circumcision of boys in the first six months of life is allowed under certain circumstances, even when not carried out by a doctor. The debate over these laws is nevertheless ongoing. Some see it as a violation of the principle of equality, while others maintain that the two problems are not comparable.

“ARE YOU ALREADY CUTTING?”, asks Ernest Chisha at the Chilenje Clinic in Lusaka. The provider – a former taxi driver upgraded to a circumciser via a two-week course – has divided Chisha’s penis up like a clock face. He clamps on forceps at 9 o’clock and 3 o’clock. Other than a dull tugging between his legs, Chisha feels nothing as the provider slices the foreskin at 12 o’clock parallel to the urethra, to get under the corona of the glans. He then cuts in a circular motion, severing the foreskin. “Done!”, exclaims the provider after five minutes, and drops the bloody piece of skin into a bucket. “Now you’re on the safe side.”

Not exactly, says the WHO. They are emphatically aware that condoms still need to be used after a circumcision. This is stressed in the training for local partners run by USAID, the authority which is coordinating the development partnership project for the US government.

“We’re not just cutting off foreskins,” says George Sinyangwe, the primary health advisor for USAID in Lusaka. The local doctor – grey suit, pink shirt, tie – has been working for the US authority since 2006. In front of him on the polished table in the conference room are circumcision brochures. An advisor – an American-educated woman with forceful hand gestures and a piercing gaze – watches over every word Sinyangwe says. “All men receive information, which totally clears up mistaken ideas about the use of the procedure, before during and after their circumcision.

“We’re not just cutting off foreskins,” says George Sinyangwe, the primary health advisor for USAID in Lusaka. The local doctor – grey suit, pink shirt, tie – has been working for the US authority since 2006. In front of him on the polished table in the conference room are circumcision brochures. An advisor – an American-educated woman with forceful hand gestures and a piercing gaze – watches over every word Sinyangwe says. “All men receive information, which totally clears up mistaken ideas about the use of the procedure, before during and after their circumcision.

But is that message about safe sex getting through?

Not to the maize farmers in Southern Zambia, at any rate. “When you have unprotected sex, your penis gets tiny cracks, into which the virus can penetrate,” explains mobilizer Margaret Nkunika to the men under the awning. “But circumcision makes your glans hard and tough.” Not a word about condoms. All the men let themselves be put on a list. When it’s full, the management will send a provider to Livingstone, the nearest large city, to carry out the operation.

“I know the protection amounts to 60 percent,” says Innocent, a 28 year-old maize farmer. “Better than nothing.”

But condoms offer a much higher level of protection! Up to 95 percent! The men laugh. Using condoms in vaginal intercourse would be like eating candy in its plastic wrapper: “You can’t taste the sweet!”

Circumcision marketing

EVERYWHERE IN ZAMBIA – in fields and on rivers, in bars, at market stalls, even on the campus of the University of Lusaka, men proclaim that circumcision liberates them from the hassle of condoms. It is like a children’s game of broken telephone: Scientists whispered their findings to the WHO, who passed it to USAID, the African governments and hundreds of NGO’s. They gave the information to their local helpers, to all of the foot-soldiers of the campaign, the mobilizers who traverse the country like Margaret Nkunika.

“Circumcision – The road to hell is paved with good intentions”

When the message finally arrives where it’s supposed to – to the maize farmers of Sichiyasa and such – crucial information has gone missing.

“If I hadn’t gotten circumcised, then I would have continued to use condoms, and I wouldn’t have AIDS now,” says Kito, 44, on the bank of the river Chongwe, an hour’s drive west of Lusaka.

The man with hollow cheeks and thin, glossy skin, he sits in the shade of a flame tree and looks over the water. Birds chirp, reeds rustle in the wind. A peaceful oasis, standing in stark contrast to Kito’s story. In 2009, at the beginning of the circumcision campaign in Zambia, Kito worked as an office assistant in the Ministry of Health. He was exposed around the clock to “the propaganda from America.” His mobilizer and his circumcision advisor both told him, “If you’re circumcised, you can’t get HIV anymore.” They were both trained by American-financed NGO’s. Kito was circumcised in Lusaka. After that, he swore off condoms. Some time later, he started having headaches, diarrhea, fever. A test revealed that Kito was HIV positive. “A world caved in on me,” he says on the riverbank.

Soon he started to visibly lose weight. Neighbours laughed at him on the street. His friends wouldn’t shake his hand anymore. After 15 years in the Ministry of Health, he was let go, on account of his HIV infection. He gradually put himself back together in a self-help group. “Thousands are just like me,” Kito lamented, “The circumcision campaign is a deadly fraud.”

A great many of recent studies warn of “mixed messages,” and the unclear information of the campaign. In Uganda, for instance, scientists at the Makere University have determined that circumcised men are more likely to take risks sexually than non-circumcised men.

In Zambia’s neighbouring country of Zimbabwe, the government has already disclosed that more circumcised men are HIV positive than non-circumcised men. Likewise in Malawi, which is also taking part in the WHO campaign; the last national health report turned out to be a disaster: the HIV rate is 30 percent higher among circumcised men than noncircumcised men.

“We’re using every means to counter mistaken perceptions about the benefits of the procedure,” says Albert Kaonga at the Zambian Ministry of Health. “Our motto is: circumcision and condoms: double works better.”

But is the rate of infection in Zambia really decreasing thanks to the mass circumcision?” Circumcision, Kaonge says, should be part of a “safety package” of various measures, including awareness-raising, HIV tests, and condoms. “The effect of circumcision alone is something we can’t calculate in isolation.”

In the circumcision room of the Chilenje Clinic in Lusaka, the provider is stitching up the wounds on Ernest Chisha’s penis. Meanwhile, on the other side of the door, eleven men sit on a low wooden bench, along with a young woman with braided hair and red earrings. In her hand, she holds a brown model penis. Barbara Luchembe spent two hours a day, for six months, completing a course to become a circumcision advisor. She correctly informs the young men that they still need to use condoms after the procedure. But a young man in stylish ripped jeans and a silver embroidered t-shirt whispers to his neighbor: “I’m only letting them cut around my thing so that I don’t need to use them anymore.”

HEALTH EXPERTS are also becoming increasingly concerned about the risks of the campaign for women. While it is true – according to the WHO – that male circumcision is supposed to reduce the risk of HIV transmission from women to men, it does not work the same in the other direction. Circumcision offers no protection to women.

In Zambia, however, this information does not seem to be getting through. On the contrary. It’s a Saturday night in Motero, a district of Lusaka. Car headlights break through the dust in the street, and the silhouettes of women appear. “You want a nice time?” Then they open their coat or robe, underneath which they are naked.

Mariam Kaoma, 40, wears high-heeled shoes, and a variety of plastic pearls on strings around her waist. On a good night she has quick sex with 12 men for 25 Kwacha – about 4 Euros. She will stay with the last man until morning for 20 Euros. “They see my pussy, and they want it live,” she says. “Live” means without a condom. And live is the most common customer request. “So I prefer to do it with circumcised men,” says Maria Kaoma later in her tiny room, containing only a mattress with pink sheets. Old dresses are piled along the damp walls. “Circumcised men are healthier. Every woman in Zambia knows that.”

In Southern Africa, the pressure to get circumcised is enormous. Posters in the streets depict a horrified African woman, tearing at her hair and shouting: “What? You’re not circumcised?” Men with intact penises are branded as disease-causing pathogens. Noncircumcised men in Lusaka now have hardly any chance of finding a female partner. “I left my boyfriend,” says Yawa, a young sociologist with a university degree, “because he didn’t want to get circumcised.” She loved him very much. Without a foreskin, the two of them could have been happy together.

An investigation in Uganda shows how fatal this development is. For women with circumcised husbands, the HIV rate in the six months after the circumcision has drastically increased – by 61 percent.

“I am absolutely convinced that some women will become HIV positive because of the circumcision of their partners,” admits French doctor Bertan Auvert – the “father of the circumcision solution” – in the scientific journal Nature, “because they fall into a false sense of security.”

But Auvert also thinks that women will benefit from male circumcision in the long run as well. If the overall HIV rate goes down first. Circumcision likewise offers hardly any protection to homosexual men, who are among the high risk groups around the world. The risk of infection from anal intercourse without a condom is several times higher than with unprotected contact between a penis and a vagina. Even the WHO only explicitly recommends circumcision for heterosexual men. At any rate, hardly anyone in Zambia knows that. Homosexuality here is punishable with imprisonment, and is correspondingly taboo.

“Most gays in Zambia think that circumcision protects them from HIV too,” says a homosexual human rights activist in Lusaka, who prefers to remain anonymous. “We are swearing off condoms and dying like flies.”

CONFUSING, FALSE, missing information? More HIV due riskier behaviours by circumcised men? “We have no indications that would substantiate such hypotheses,” says George Sinyangwe of USAID at the conference table in Lusaka. His advisor nods calmly. But how can that be? How can one ignore the facts in the health report from the neighbouring country of Malawi, where circumcised men are already showing higher HIV rates than non-circumcised men? Or the other alarming studies?

Sinyangwe won’t let himself be swayed. “We’re on the right track.”

Perhaps the national health report of Zambia could give clearer information about the effects of thousands of circumcisions. But the complete set of figures has not appeared since 2007.

WHY would a government go flying blind like this? In Zambia, more than three quarters of the country’s population lives below the poverty line. The aid industry which has emerged out of the AIDS epidemic is the second-largest employer, after the government. “When millions of aid dollars are being pumped into the country, nobody asks questions,” says parliamentarian Elias Chipimo. “All proceeds are accepted with open arms – whether the measures they pay for accomplish anything or not.”

Critics attest that the WHO campaign is a colonial holdover that subordinates Africans as a group; it implies that they’re incapable of changing their sexual behaviour and using condoms. And now even babies are being circumcised – above all to burnish the quota, believes Edith Nawakwi, president of the Forum for Democracy and Development in Lusaka. Whether or not the babies are in agreement with the irreversible procedure, they naturally can’t do anything about it. And yet even UNICEF, the children’s aid organization of the UNited Nations, is fully on board with circumcision. “With one quick cut,” says Edith Nawakwi, “the bodies of Africans become a playground for Western foreign aid.”

In the high security complex of the WHO in Lusaka, the chief administrator crosses his arms in front of his chest. “You won’t get a word out of us,” says the American in the blue and white striped shirt. “Nobody here wants to say the wrong thing.”

Silence from the World Health Organization (WHO)

WALLS. SILENCE. Continuing on. But why? Why are USAID, the WHO and the United Nations risking a catastrophe? Why don’t they dedicate their massive budgets to making condoms popular? Zambian politicians like Nawakwi and Chipimo see the mass circumcisions as an expression of deep frustration on the part of Western foreign aid. The goal of changing complex human behaviours – the most essential component in the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases – has been given up in favour of technocratic solutions like circumcision.

“That makes it easier to show off initiatives and successes, especially to donors,” says Chipimo. “Behaviour change is a vague business. Circumcision, on the other hand, delivers impressive numbers of cut-off foreskins, and high-quality photos of clinics, helpers, medical equipment – this keeps the dollars flowing in.”

The WHO remains nebulous: the organization’s Geneva headquarters do not reply to written inquiries.

IN HIS PRACTICE on Sylt, the urologist Wolfgang Bühmann shakes his head. “The worst thing about it, is that the primary reference studies for the WHO are full of errors.” The Australian circumcision expert Gregory Boyle of Bond University in Queensland shares this opinion. He attributes to the WHO studies a whole array of scientific errors, above all inadequate balance, skewed selection of test subjects, and distorting important details.

It is true that the three clinical studies which are held out as proof for the effectiveness of circumcision did work with control groups just as the rules for solid research work demand. Although, the circumcised participants in the study were unable, on account of their wounds, to have sex for at least six weeks following the surgery. “The uncircumcised men in the control group did not require this period of abstinence,” explains the Urologist Bühmann, “and during this time were at a correspondingly higher risk of infection.” This, among other things, distorted the results.

On top of this, the study conducted by the Frenchman Auvert – originally set up to last 21 months – was broken off early. The results, it was said, were already clear. To continue the experiment would have been ethically unacceptable, because this would have meant an increased risk of death for the uncircumcised control group.

Could be. But in the view of international experts like Michel Garenne, researcher at the renowned Pasteur Institute in Paris, the study was broken off much too soon to offer conclusive justification for surgical interventions on millions of people.

ADDITIONALLY, according to the critics, the trials are based on far too few subjects. Also, a significant number of those who later tested HIV positive did not contract the virus sexually at all, but via contaminated needles, blood transfusions, and surgical instruments – a lack of clarity that the researchers did not take into account. Many participants also simply disappeared, and ultimately could not be tested or asked any questions.

“From a scientific point of view, the reference studies for the WHO are a catastrophe,” the urologist Wolfgang Bühmann concludes. The so-called circumcision solution is anything but a solution. Likewise Robert Van Howe MD,MS, FAAP, professor at Michigan State University, who has been researching this issue for years, is convinced: “The circumcision campaign will ultimately increase the number of HIV infections.”

ERNEST CHISHA knows nothing about all of this. The provider in the Chilenje Clinic dabs the blood off his freshly stitched penis, wraps it in a bandage, and sticks it against his stomach with tape. Then Chisha heads back out into his life, with a few pain tablets in hand and a belief in the incredible power of circumcision.

The army of foot-soldiers in the campaign against AIDS are also unaware. “I preach the Word of circumcision like a pastor preaches the Word of God,” says mobilizer Margaret Nkunika.

George Sinyangwe of USAID runs his hand over his short-trimmed beard. His organization is responsible for hundreds of thousands of circumcisions in Zambia alone. “We know exactly what we’re doing,” says Sinyangwe, and straightens the knots in his tie at the conference table. The US government will press on with the campaign, “We’re doing extraordinary work here.”

But what about the indications of more HIV infections in certain segments of the population? The warnings of international experts? “We don’t comment on the critical opinions of scientists,” says Sinyangwe. Instead, he holds up his brochures: circumcision rates, bar graphs, success curves. 2015 will be especially good: 1.9 million removed foreskins.

So is the Zambian doctor himself circumcised?

Sinyangwe’s face suddenly turns to stone. His eyes are wide, his mouth open. “No,” he finally says, softly. He hesitates. His advisor presses him “Say it, say that you’re planning on it,” she tells him. Sinyangwe looks past the edge of the table, between his legs. “No!”, says the man from USAID again.

Author: MICHAEL OBERT

After returning to Germany, Obert tried for weeks to obtain an official statement from the World Health Organization. He received no response.

Leave a Comment